I have a confession to make: I didn’t want to write this post. What can I possibly say to express the magnitude of my appreciation for you without acknowledging the current moment and thereby wading into the political—something I’m neither supposed to do, nor want to?

But that’s been true for everything I’ve written or recorded for you this year. Every single message has been so hard to compose. I’ve obsessed over every word.

This is not my norm. I rarely struggle to find my words, especially when talking to teachers. You are my people, and I’ve always found it easy and natural to communicate with you. This year is different, not because of you, but because of the extraordinary circumstances in which you find yourself trying to teach for the maintenance of our constitutional democracy.

But here we go…

I appreciate you. All of iCivics appreciates you: our staff, our board (including Justice Sotomayor!), and our donors appreciate you.

And even though she is no longer with us, and I wouldn’t dare to put words in her mouth, I’m certain Justice O’Connor is smiling down upon you with awe and appreciation. We are all so grateful.

As the Chief Education Officer at a nonprofit organization, I necessarily wear a lot of hats. I know you get it. You do too.

You’re not just history or civics teachers. You’re counselors, coaches, club advisors, hallway monitors, test proctors, lunchroom attendants, and sometimes traffic directors. Every day when I drop my daughter off at school, I’m filled with both gratitude and cognitive dissonance when I see teachers with graduate degrees wearing professional clothing while blowing whistles and managing car lines in the south Georgia humidity.

That is insane. No other profession asks so much in the form of “other duties as assigned.”

My job description encapsulates many different things—important things, like academic integrity, impact research, youth engagement, and more. But my number one priority right now is supporting you in any way I can—not because you need my help, but because you need a friggin’ break.

So this is both a letter of appreciation and an invitation to HIT.ME.UP. Not to go to the club, although drinks are on me if we find ourselves in the same city. No, hit me up for what you need. How can I help? How can the team at iCivics make your job easier?

Because appreciation without action is like a terrible hug: hollow, unsatisfying, and oftentimes awkward.

We’re not here for that. We’re here for genuine, authentic appreciation—the kind that feels like a hug from your best friend after months or years apart.

Here’s what we’re doing at iCivics to put our appreciation into action:

- We are LISTENING. As much as I want to delete all of my accounts, I continue to stay engaged on as many social media sites as possible to understand your daily struggles. The same is true for our marketing, product, and professional Learning teams. We’re also on a listening tour, scheduling 1:1 virtual meetings with educators.

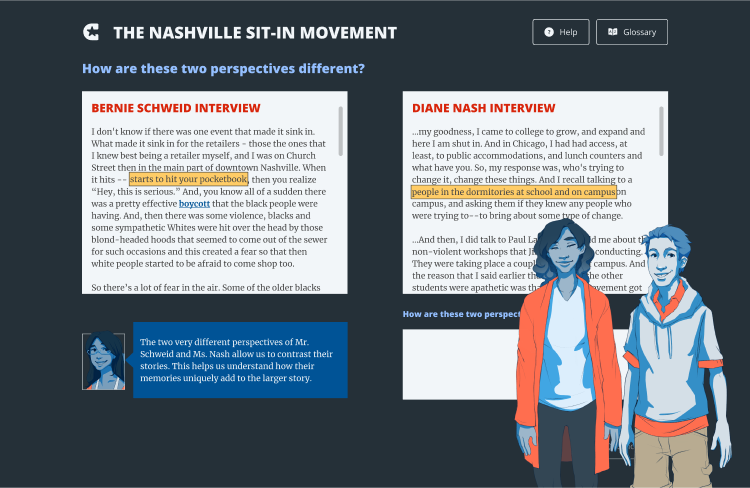

- We are CREATING. Every day, the award-winning product team at iCivics is researching, writing, revising, and uploading so that you have access to accurate, objective, engaging, and impactful resources.

- We are ADVOCATING. Our Policy team is tracking bills, calling legislators, convening state-based commissions, and doing everything else in its power to ensure that states propose and pass bills that support civic education and civic educators.

- We are PLANNING. We have our eyes on Constitution Day in September, NCSS in December, Civic Learning Week in March, and America250 from June 2025 to July 2026. We’re hard at work to make these special occasions and opportunities as meaningful as possible.

With that, I send you my biggest virtual hug—one that feels like a hug from veteran educator and iCivics Educator Network member Shannon Salter from Pennsylvania. Shannon gives the best hugs. They are whole-body, perfectly forceful, and just long enough for you to feel her affection without bystanders starting to wonder if something else is going on or if they should intervene. That’s the kind of hug I’m sending you.

With all of my gratitude,

Emma

P.S. We want to hear from you! Really, how can we help?

Here are some ideas that come to mind, but we are all ears for your specific suggestions:

Written by Emma Humphries

Dr. Emma Humphries, iCivics’ Chief Education Officer, brings extensive classroom experience teaching government, history, and economics, where she discovered the impact of engaging learning tools. With a deep commitment to empowering educators, she continues to champion innovative civic education resources and strategies.