In my 21 years of teaching middle school, I have experienced many PD sessions and received countless books, tech apps, teaching “guides,” and “supports” from administration. Very few of these have truly improved my life or my professional practice. (Perhaps you can relate?)

The ones that were valuable had one thing in common: they solved a problem. They didn’t cause more work for me; they reduced my workload. They were not just cutting-edge flashy fads; they offered real shortcuts and long-lasting solutions.

As I’ve taken on the new 8th grade civics project requirement the past few years, I have experienced many problems…and I finally found one solution to all of them: the iCivics workbook.

Here are five problems that the iCivics workbook helps resolve.

Problem 1: Dealing with Reality

Stuff happens, and we know to expect the unexpected (school assemblies, illnesses, new students moving in, global pandemics, etc.). As I’ve learned the hard way, civics projects can get stalled or accelerated at any time by a single email reply, a guest speaker visit, or another real-life development.

iCivics’ Solution: Their curriculum material never prescribes a certain amount of time for each lesson, and it does not presume that all your students in a class are working on the same project. The lessons and activities are deliberately ambiguous: “you” could be an individual student, a small group, or the entire class. This leaves it up to you [the teacher] to divide students however you like. They could split into groups halfway through the project, or a single student could “go rogue” with their own project idea and continue following the workbook.

In terms of daily implementation, there is also a lot of leeway. You could have whole-class read-alouds of the text on workbook pages, or assign them as homework, or some combination. (This links back to the solution to Problem 3: the passages and activities are generally accessible to everybody for independent success.) If a class discussion or guest-speaker visit goes longer for one group than others, you could let them catch up by reading or doing a certain page of their workbook before tomorrow’s class. Hooray for simplicity!

If you get squeezed for time near the end of the unit*, then perhaps some or all students don’t reach Stage 6 (“Reflecting and Showcasing”). That’s OK, because, in my humble opinion, that is the least important aspect of the project. Implementing their action plan from Stage 5 could be a success in itself, with no glitter glue or slide transitions required.

*If that’s never happened to you, then please let me take you out for a drink or coffee so I can learn your secrets of success! Haha, just kidding; of course, this has happened to you.

Problem 2: Properly Pacing the Project

In my experience, students usually take too long choosing their topic and then go too fast in developing their plan — often they even meld the two steps together in the early days of the project: “Let’s make an Instagram account right now to tell people about the city’s recycling program!” Whoa, whoa there, kids, let’s think this through. When you are leading this project for the first time, it is tough to know when to push the class along versus when to let them marinate on a decision, especially when you are developing most of the material yourself.

iCivics’ Solution: Many pages in the workbook prompt students to slow down, think carefully, seek multiple solutions, and evaluate possibilities. Lesson 3.2 “Who You Gonna Call?” is not about busting ghosts; it’s about considering the differences between individual, group, and government actions to a community problem. At the end, students are prompted to determine which would be the best approach to a scenario and explain their answer. Twelve pages later, they apply the same judgment to their real-life topic, which should lead them to a well-selected government action as their project’s plan.

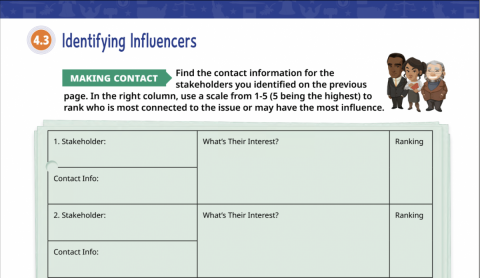

Page 76 is another good example, where students list potential influencers and rank their connection on a 1-5 scale. That should prevent them from just contacting the first people they think of.

For situations where you need to nudge the class forward, set a time limit for completing a certain page. In certain cases, you might have to take Executive Command to break the logjam. Later on, everyone can turn back to that workbook page to judge the value of that decision. Also, I think it’s valuable to have a physical workbook where you can point forward through the text: “Look, folks: we’re on page 28 and there is a lot more work left to do!”

In case you’re wondering, social media campaigns first appear on workbook page 78, and there is a “Build Your Toolbox” activity page that forces students to carefully consider the value of tactics like creating an Instagram account to spread awareness. Maybe, just maybe, that’s not the best bet.

Problem 3: Effective Organization

The wonderful & terrible thing about civics projects is that they are real-life efforts. That means things get messy & complicated quite quickly, especially when you are juggling multiple groups and/or classes. I have literally lost sleep at night trying to keep everything straight, and developing then re-developing organization systems for classwork. Without a strong structure, everything will collapse like a house of cards.

iCivics’ Solution: The workbook lays out six stages that provide structure by “starting wide” at the community level, then guiding students to narrow their focus toward a single issue, developing skills to research that issue in multiple ways, seeking outside help from influencers and decision-makers, and finally designing their “pitch” to persuade productive action. In reality, it is not as simple as that sentence makes things sound, but the workbook is chopped into lessons (3-6 pages and 1-3 class periods each) that build on each other. You might be able to skip one or more lessons, depending on your students’ prior knowledge and the project topic they select, but you probably won’t need to add anything.

Furthermore, I cannot overemphasize the value of having a single container for all the lessons and most (maybe all) of the students’ academic output, notes, and reflections … instead of grappling with loose papers all over the place and/or clicking through dozens of shared GoogleDocs! That is a very big One Less Thing.

How do you grade each student fairly, especially if you’re running a whole-class civics project? Assigning quizzes seems time-consuming, and waiting until the end for a formal unit test probably doesn’t seem great either. And what are you actually supposed to assess, anyway?!

iCivics’ Solution: In the workbook, each of the six stages has a 4-column rubric at the end where you can individually mark students’ progress on the activities. You could also re-create that iCivics chart as a Google Sheet, a rubric in your LMS, or whatever else works for you. Personally, I prefer assigning open-ended reflections throughout the project. That is also built into the workbook, with at least one prompt per stage. Each lesson in the Teacher’s Guide has a header of learning objectives that remind you about the skills & knowledge that could be assessed after the activities. That will help avoid the common syndrome of Oh My Gosh Everything Matters Paralysis.*

For example, lesson 3.3 addresses the differences between government regulations vs. provisions and restrictions vs. benefits. If students don’t get those terms straight, remember that the main purpose is for them to identify “tax-supported facilities and services” — not a perfect record of distinguishing types of service. Let’s just make sure that kids know there are multiple specific ways for local & state governments to impact people’s actions. In the “Apply To Your Issue” workbook page at the end of that lesson, students should be able to successfully identify at least one potential government solution to the problem they’ve been researching. BOOM! Mission accomplished.

*OMGEMP is a serious condition. Side effects include nausea, insomnia, muscle spasms, and caffeine addiction. If symptoms last for longer than 24 hours, seek professional attention.

Problem 5: Finding Age-Appropriate Curriculum Material

Real-life civics projects are challenging enough without pausing every two sentences to define a half-dozen vocabulary words, dangit! All the other existing teaching guides that I’ve seen are geared toward high-school students in terms of reading level and conceptual framework. The curriculum that my school district has used the past few years needed a lot of modification to work for all our 8th graders, to the point that we were basically re-designing the whole (expensive) thing!

iCivics’ Solution: The Civics Projects workbook is student-friendly in terms of page layout, font size, and overall approach.

For example, I really like the several stories that run through the six stages, like Amir’s project which introduces the concepts of influencers and stakeholders, then reappears 20 pages later as the basis of the “speech sandwich”. The spiraling of examples & concepts will definitely work for my 8th graders, and I imagine it would for high-schoolers, as well.

I also greatly appreciate the skill-building pages like “Research Time” in Stage 3, and the appendix pages for “Surfing Success” and “Finding SMEs.” These could be helpful reminders of previously-learned skills, or a really good introduction to concepts of media literacy and source selection — depending on your students’ needs and experience. These are some of the elements I had to add myself when I used a different civics curriculum (which shall remain unnamed).

I am not a textbook or workbook person. I have always been more of a “control enthusiast,” like Patrick Warburton in those rental car ads: producing and redesigning my own teaching material pretty much all the time. However, it pains me to admit that with the civics project there were too many problems I could not solve myself. The Civics Projects workbooks are the only curriculum guide I would ever use from cover to cover.

If you would like to use iCivics’ workbooks to assist with implementing civics projects in your classroom, check them out by clicking the button below!

Written by Andrew Swan

Andrew is an 8th grade Social Studies teacher at Bigelow Middle School in Newton MA, where he has worked for 17 years. He has been a member of the iCivics Educator Network since 2019 and served as a reviewer of the iCivics workbook. Andrew is also a co-moderator of the popular SSChat Network that hosts weekly social studies chats on Twitter with the #sschat hashtag. Follow him at @flipping_A_tchr.