The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.

—The Constitution of the United States. Art. II Sect. 1 cl. 1

Teaching executive power can be daunting in any political climate. Its scope is contested, oftentimes along political lines, and the Constitution offers minimal explicit guidance. Moreover, the powers of the President have evolved—mostly by expanding—throughout history, rendering the office almost unrecognizable from the office of the 1800s and even into the 20th century.

While the powers of Congress are explicitly stated (with the exception of clause 18), presidential powers are not. In outlining the legislative branch, the Founders drew on examples of citizen councils and representative bodies from throughout history, even drawing on their own experience with the Articles of Confederation. They benefited from real-life examples of various models as they sought to determine the best system for our young nation.

The same cannot be said for the executive branch. Instead, the Founders’ preferences were shaped by their experiences during Shays’ Rebellion and other early challenges facing the Continental Congress, such as collecting taxes, regulating commerce, and enforcing treaties. That said, they knew what they didn’t want: an executive with unlimited power and authority, akin to a monarch or dictator.

To learn about executive powers in my classroom, students conduct a side-by-side comparison of Articles I and II, allowing them to identify critical differences. The contrasting language, length, and breadth across the two articles provide insight into the Founders’ understanding and expectations of executive power, and students often arrive at some common conclusions.

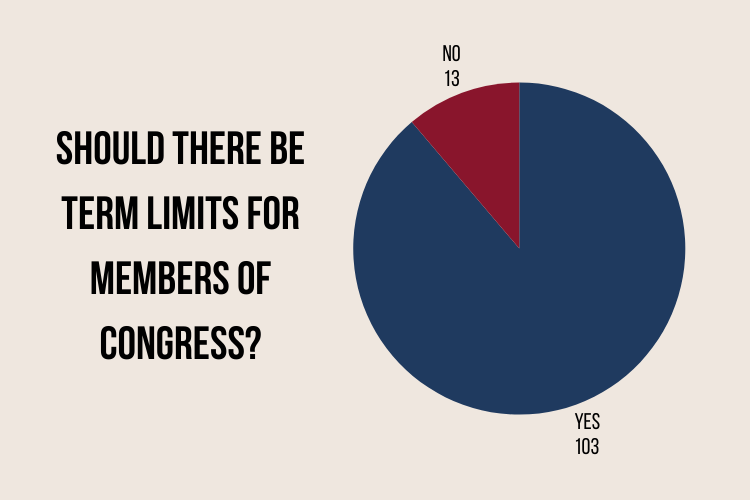

We discuss how the office of the President is unique in that it is shaped by custom and tradition, the voice of the people, and checks from the other branches. Many of the limitations on presidential power arise after a president has attempted to extend their power beyond that of their predecessors. The example I use with my students comes from the ratification of the 22nd Amendment in 1951. We discuss the unofficial precedent set by George Washington, who served only two terms, until F.D.R. ran and won the office four times. What was once a custom became codified in the 22nd Amendment when the people decided a president should be limited to two terms.

We also discuss the changing scope of presidential power throughout history. I use F.D.R.’s Executive Order #9066, which was the removal and relocation of Japanese Americans to internment camps. I usually lead a discussion on the content of the order and its effects on the population. My next question to my students is, “If this action is constitutional, why hasn’t another president used this power?” Inevitably, my students conclude that the president would not likely be able to enact this power at this moment in time. I always follow up with “why?” They discuss the idea that this particular action would not be popular with the general population. After that, we discuss Richard Neustadt’s famous phrase, “presidential power is the power to persuade”. We also discuss the evolution of executive orders from simple directives to having “law-like” significance, such as the Emancipation Proclamation.

My students and I study presidential powers from a neutral observer perspective with the analytical lens of a political scientist. By adopting this observational stance, students can set aside their personal feelings regarding a person, a party, and specific issues. They then become a class of political scientists. As Hamilton states, “the people are the only legitimate fountain of power, and it is from them that the constitutional charter, under which the several branches of government hold their power” (Hamilton 1788, Federalist #49).

Resources to Use:

- Lesson Plan: Why President?

- Infographic: The Six Roles of the President

- Lesson Plan: The Second Branch

- Video: Faithfully Execute

- Lesson Plan: The Modern President

- Infographic: Order Up! Executive Orders

- Game: Executive Command

Written by Brittany Marrs

Brittany Marrs is a certified social studies educator with extensive experience teaching AP Government, AP Macroeconomics, Dual Credit Government, Dual Enrollment Microeconomics, and Economics at Magnolia High School in Texas. With a background in political science and law, she is passionate about empowering students to think critically, engage civically, and understand the institutions shaping their world.

Brittany is actively involved in numerous professional and community organizations and is currently pursuing National Board Certification in Social Studies. She is dedicated to developing meaningful assessments and creating inquiry-based classrooms. When she’s not teaching or writing, she is often collaborating with other educators to strengthen civic education and promote student voice. She has been a member of the iCivics Educator Network since 2021.

Through the We Can Teach Hard Things initiative, the perspectives of teachers across the country contribute to the public conversation about civic education in the United States. Each contributor represents their own opinion. We welcome this plurality of perspectives.