"The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice."

Theodore Parker

That’s not a typo you see in the attribution above. While the oft-cited quote is chiefly credited to Martin Luther King, Jr., who did indeed speak those brilliant words during more than one speech, it was originally coined by 19th-century Unitarian minister and radical abolitionist from Boston, Theodore Parker.

Sources matter, especially in a blog post that promotes primary sources to teach civil rights. But first, why are we talking about civil rights in a series dedicated to “teaching hard things” — a series predicated on teaching traditional civics topics that have become controversial in this moment or in response to current events?

I’ll admit: civil rights wasn’t on my radar when we first conceived the “We Can Teach Hard Things” series. I was thinking more about the rule of law, due process, separation of powers, immigration, citizenship, and other government-related topics that have dominated recent news cycles. I wasn’t thinking about slavery, the rise of Twentieth-Century fascism, or the civil rights movement. But when we asked teachers, these topics kept being mentioned. Thus, here we are. Let’s talk about teaching civil rights.

We often teach history as eras, movements, or moments in time, and civil rights is no different. The phrase immediately conjures images of 1950s-60s America, and if you locate it in the index of a high school textbook, the page number will surely bring you to a chapter covering these decades. In other words, folks could be forgiven for mistakenly assigning it to a finite period in our nation’s history.

We know better. We know civil rights represents a tapestry we’ve been weaving since the very beginning of our nation, and we are certainly not done. In this way, civil rights is aspirational. It is also, I believe, inspirational. Nowhere is this truer than in the primary sources comprising the Americana canon.

WE hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal.

Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate, only love can do that.

The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.

Of all the great speeches, poems, letters, and more, the one that has always touched me the deepest is Frederick Douglass’ famous (and famously long-winded) What, to the slave, is the 4th of July?

In the opening sentence of his fourth of 71 (!!) paragraphs, he asks and answers his stinging question: “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. . . .”

He continues his speech. Oh, boy, does he continue. It is scathing. It is raw. It is unflinchingly honest. Douglass pulls no punches.

I know what you’re thinking, “How is that inspirational or even aspirational?”

Stay with me. Stay with Douglass. His hope emerges in stark relief in his closing:

[. . . .] the Constitution is a GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT. Read its preamble, consider its purposes. Is slavery among them . . . While I do not intend to argue this question on the present occasion, let me ask, if it be not somewhat singular that, if the Constitution were intended to be, by its framers and adopters, a slave-holding instrument, why neither slavery, slaveholding, nor slave can anywhere be found in it. . . . I hold that every American has a right to form an opinion of the constitution, and to propagate that opinion, and to use all honorable means to make his opinion the prevailing one. . . .

Now, take the Constitution according to its plain reading, and I defy the presentation of a single proslavery clause in it. On the other hand it will be found to contain principles and purposes, entirely hostile to the existence of slavery…

Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country. There are forces in operation, which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery. ‘The arm of the Lord is not shortened,’ and the doom of slavery is certain. I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope. While drawing encouragement from the Declaration of Independence, the great principles it contains, and the genius of American institutions, my spirit is also cheered by the obvious tendencies of the age. . . .

When I think of Douglass’s speech in its entirety, I view it as the embodiment of what Alexis de Tocqueville referred to as “reflective patriotism.” In the Educating for American Democracy (EAD) report, reflective patriotism is described as “appreciation of the ideals of our political order, candid reckoning with the country’s failures to live up to those ideals, motivation to take responsibility for self-government, and deliberative skill to debate the challenges that face us in the present and future.”

Here are a few tips for making this speech, or any other source from the deep and wide library of American civil rights thought leadership:

- As always, be sure to consult and follow your state standards, plan for a structured lesson with clear objectives tied to those standards, and communicate with stakeholders ahead of time if you have any reservations.

- If you’re using Douglass’s speech or any other source from the 19th or 20th Century, you’re already following two pieces of guidance for teaching hard things: using primary sources as “grounding texts” and using historical examples instead of current ones. I would also suggest adopting an inquiry-based approach. A great focus for Douglass’s speech is the concept of distance. Perhaps you might ask, “How does Douglass use the concept of ‘distance’ to explain why he cannot join the Fourth of July celebrations?”

- Don’t be afraid to “tamper with” the document — to alter it in ways that make it more accessible to students. Douglass’s speech is over 10,000 words long, and that’s only part of what makes it so daunting. I suggest following the advice of Sam Wineburg and Daisy Martin (2009)* and focusing, simplifying, and adjusting the presentation of the source. Shorten it. Cut or replace confusing words. Use a large font size, provide ample white space, and don’t be afraid to italicize critical points or provide a vocabulary legend. Sure, the purists may decry your “assault” on the original brilliance of the source, but between that and never showing it to students at all, I’m willing to face their criticism.

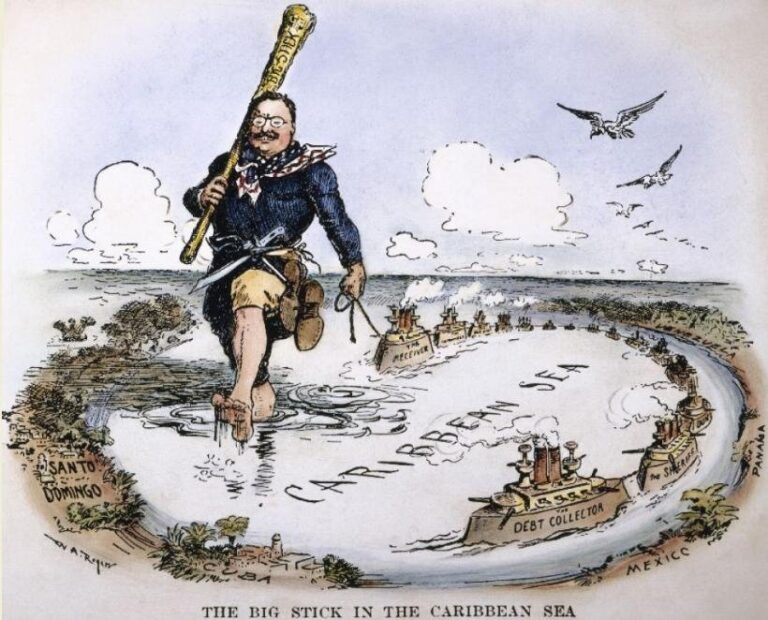

Something worth noting is that Douglass follows our guidance to focus on the office or institution rather than the person or party. He refers to lawmakers, the President, the Secretary of State, Congress, the Continental Congress — his is not an indictment of any person or politician so much as it is a nation struggling to live out one of its highest ideals: equality.

Our students deserve an education rich in this philosophy, and few topics in our discipline provide the seeds for this rich soil as much as civil rights. Yes, civil rights can be hard to teach, so lean into the primary sources that have paved the way toward our more perfect union. While many of their authors were surely not viewed as patriots in the 1850s or the 1950s, I challenge anyone today to tell me that Martin Luther King, Jr., Frederick Douglass, and Ida B. Wells were anything but.

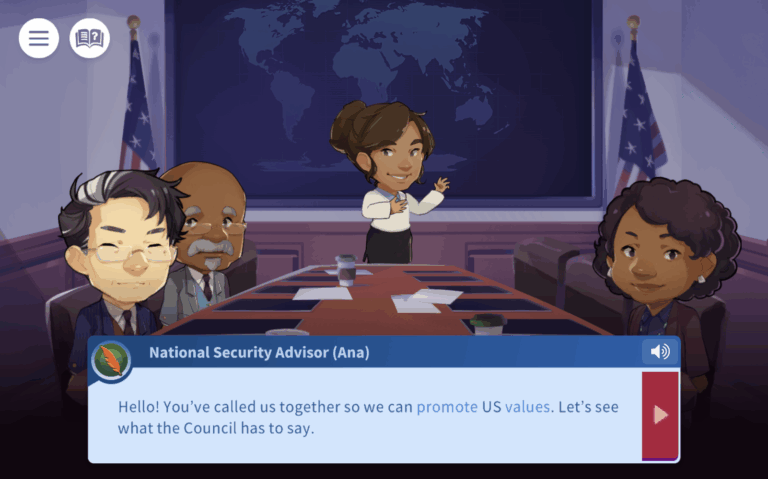

iCivics has an entire unit dedicated to civil rights, but here are some of my favorite resources.

- DBQuest: Resisting Slavery or The Nashville Sit-ins

- Videos: Breaking Barriers series

- Infographic: A Movement in the Right Direction

- Private i Inquiry (Elementary): Why do Many People Celebrate on the Fourth of July?

Admin Tip: It doesn’t take much to inspire and empower your weary history and civics teachers. A simple, “I’m really excited for our students to learn about civil rights from you,” would go further than you can imagine.