You’re a social studies teacher, and it’s time to teach the separation of powers. Easy peasy! The Separation of Powers is as fundamental a civics topic as can be found. No controversy here!! *record scratches*

Don’t worry! I’ve got you covered.

The first thing you want to do is consult your state standards. Let’s use an example. Since my favorite crises of the Separation of Powers revolved around Senator Joseph McCarthy from Wisconsin, let’s go with the Badger State!

According to Wisconsin’s Standards for Social Studies, students in grades 6-8 should “Analyze the structure, functions, powers, and limitations of government at the local, state, tribal, and federal levels.” Students in grades 9-12 should “Evaluate the structure and functions of governments at the local, state, tribal, national, and global levels. Evaluate the purpose of political institutions at the local, state, tribal, national, global, and supranational or NGO levels, distinguishing their roles, powers, and limitations.”

There you go — if you teach in Wisconsin (and most other states), it’s absolutely part of your job to teach this topic. Remember that.

Moving beyond standards, one of the best parts about teaching government is that many of its concepts are structural or procedural and abstract. One of the worst parts is that many of its concepts are structural or procedural and abstract.

Put another way, on one hand, we merely need to explain and describe. It’s pretty straightforward. On the other hand, these concepts are dry, emotionless, abstract, and otherwise difficult for students to fully grasp.

Here’s the good news, which is also the bad news: in practice, most government concepts are not straightforward. They are complex and controversial.

What’s a dedicated, well-meaning teacher to do?

Let’s start by looking at the bright side (this stuff is structural and procedural!!) and leverage one of our go-to tips: “Leaning into structure and process for civics and government.”

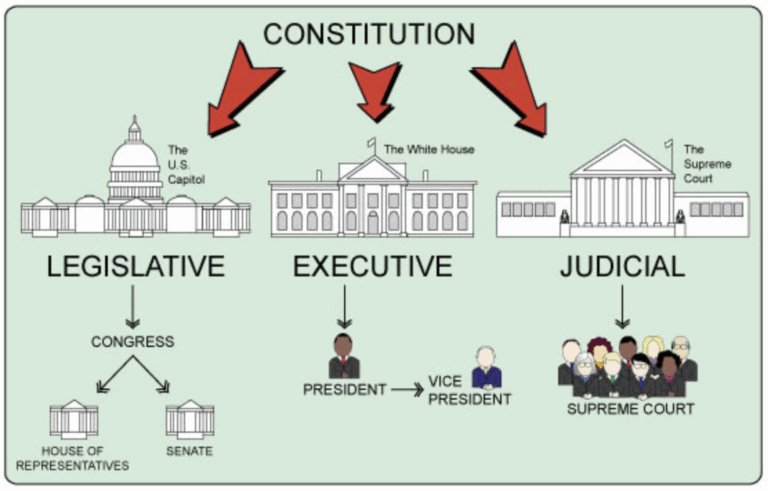

With the separation of powers, it’s actually best to start with structure and then move to process. Structure is even easier to explain, especially since we can use actual structures as symbols of the institutions we’re describing. Take this graphic:

This graphic is so old, I think my own government teacher used it in 1999 when I was in her class. But it’s great! It’s perfect! It’s listed under a Creative Commons license. Phew!

Here are some additional iCivics Resources to help you through it, should you (appropriately) believe this graphic to be inadequate:

Now, you may feel tempted to avoid the hard things and end your lesson here. But remember, the standard says, “Analyze the structure, functions, powers, and limitations of government.” I suppose you likely scratched the surface here with functions when you talked about the Legislative Branch making the law, the Executive Branch enforcing the law, and the Judicial Branch interpreting the law, but a) that doesn’t cover powers and limitations, and b) none of that means anything to your students without context and examples.

This brings us to another go-to tip: Use historical examples instead of current ones. Various events in American history have tested the limits of the Constitution’s separation of powers. These events demonstrate the ongoing tension and potential for conflict between the different branches of government.

Here are some of my favorite examples of the separation of powers playing out in American history:

- The New Deal

- FDR’s Court Packing Plan

- Steel Mill Seizure

- The McCarthy Era

- The Civil Rights Movement

- Watergate

- The Iran-Contra affair

Additionally, these events allow us to examine the separation of powers and controversies surrounding it without the partisan preferences and emotions that often accompany more recent or current controversies. I mean, I know my history, but I don’t get all worked up over President Truman seizing control of the steel mills to prevent a devastating strike that would disrupt military production during the Korean War, even if it does seem like a reach of executive power. Let’s assume our students won’t either.

Once we’ve covered the structure, functions, powers, and limitations, and provided some historical examples, it’s time for the students to think about what it all means. That brings us to…

Important Questions to Ask

- What do we mean when we refer to the separation of powers as a system of checks and balances?

- Can you think of an example when it might be necessary for one branch to exercise more power than the other branches?

- What would happen if too much power were concentrated in one branch of government without checks by the other branches?

Now, I know what you’re thinking: “What should I do if Susie in the front row responds to that last question by asking, ‘Do you mean like how the President is acting right now?’”

This very thing happened to me when I was teaching in the 2000s. Here’s my advice:

- Take a breath.

- Acknowledge the question, but don’t validate, correct, or otherwise answer it.

- If you’re so inclined, praise the student for paying attention to current events (and to your lesson!).

- Don’t assume anyone else in the classroom knows what Susie in the front row is talking about. This point is extra important! There is no need to spend valuable class time having an unplanned 1:1 conversation with just one student when no one else in the room has the foggiest idea what y’all are talking about.

Here’s a sample response: That’s a great question, Susie. I can tell you’ve been paying attention, both to the news and to what we’ve been exploring in class. The current administration has been in the news a lot, and its actions are related to what we’ve been covering. We’re not going to talk about current events right now, but here’s something for you to think about as you continue following the news: “What exactly is happening right now, and is this how it’s always been done? How is it similar or different?”

Alternatively, you could ask these questions preemptively and suggest that students follow the news, consider the questions, and discuss them with fellow students and/or family members. I realize that last suggestion may seem a little risky, but remember: you haven’t made any political or value judgments. If anyone challenges you, you can confidently and politely respond that you are encouraging students to engage in compare and contrast thinking between historical and current events, and that you’re so glad to know they’re doing their homework!

Remember: you’re doing your job, and your job matters a whole lot.

Admin Tip: Reach out to your social studies teachers and ask if they need any additional help with content this year. Maybe a subject matter expert can help them understand how the separation of powers has evolved over time. As always, tell your social studies teachers you are there to support them!

Then they must identify the Constitutional arguments used to support the argument. Once identified, they must build an argument based on Action cards and Support cards. They offer a rebuttal to the opposing side by quickly choosing correct supporting arguments. This game’s strength lies in the variety of gameplay. Not only can you choose between several cases, but you can also choose which side to support and the argument to build. You cannot simply click your way through the game successfully. It takes reading and critical thinking skills to make your way through, but it is not at such a difficulty level that the average student would quit out of frustration.

Then they must identify the Constitutional arguments used to support the argument. Once identified, they must build an argument based on Action cards and Support cards. They offer a rebuttal to the opposing side by quickly choosing correct supporting arguments. This game’s strength lies in the variety of gameplay. Not only can you choose between several cases, but you can also choose which side to support and the argument to build. You cannot simply click your way through the game successfully. It takes reading and critical thinking skills to make your way through, but it is not at such a difficulty level that the average student would quit out of frustration. and in the years since, I am continuously surprised by how few people have heard of it! Keeping the name of Supreme Decision, iCivics took the original storyline and developed a truly interactive simulation through the decision-making process.

and in the years since, I am continuously surprised by how few people have heard of it! Keeping the name of Supreme Decision, iCivics took the original storyline and developed a truly interactive simulation through the decision-making process.