The 2000 presidential race was the first election veteran teacher Shari Conditt taught about, and she’s learned a lot since then. In her more than 25 years of teaching, Shari has taught through seven presidential elections, six midterms, and many local elections.

“Elections are always tricky,” Shari said. “It doesn’t matter which election we’re talking about, really. Even midterms are tricky. With that said, I think presidential elections tend to feel a bit more divisive—and not just on sort of a regional level like you might feel when you’re talking about a local election or the House of Representatives, but rather sort of on the national level because of the amount of media attention that’s garnered through the election. And because of that, there’s a domino effect, and it trickles down to students.”

Last year, with political tension high and the country once again divided, Shari and her team of tight-knit social studies teachers at Woodland High School decided to approach election instruction with a plan, and iCivics was at the heart of it.

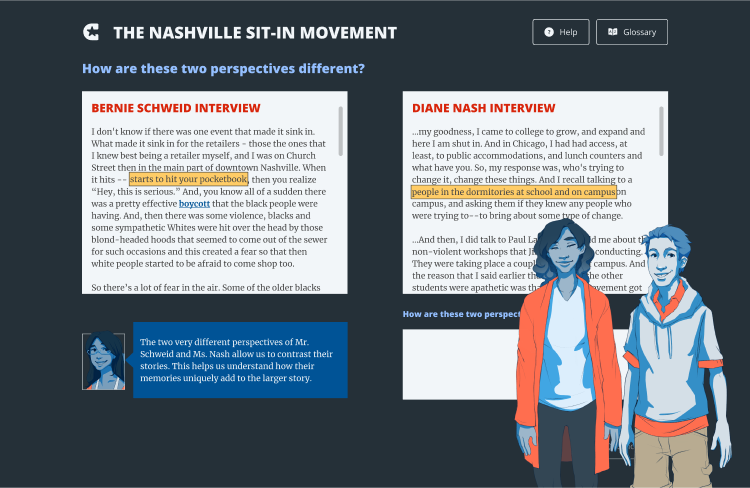

“I need to be really thoughtful about how I maneuver through students’ questions by maintaining a nonpartisan, neutral lens and ensuring that I’m providing the resources that students need in order to come up with their own opinions, without necessarily indicating where I might stand on any sort of issue. And iCivics helps me do that.”

The team curated a set of nonpartisan resources, lesson plans, and talking points not just for their own classrooms but for educators across the school and even in their middle school. They gave all teachers these materials because they knew students would have questions about the election in places outside of their social studies classrooms.

At the center of this toolkit were iCivics materials like the Popular vs. President lesson, which helps students understand the relationship between the electoral vote and the popular vote. They also made use of iCivics games like Win the White House to engage students in learning about the election process through interactive simulations.

One of the most powerful aspects of iCivics for Shari is the peace of mind it brings. “iCivics allows me the opportunity and materials to live in a nonpartisan place. There’s nothing about them that opens the door to a political agenda or to policy issues, and they really focus on the things that I, and we, want fidelity to: sustaining our democracy.”

Shari zeroed in on systems thinking: electoral processes, media literacy, and constitutional frameworks. She made it clear that she operates from a party-neutral position and provides high-quality, nonpartisan resources. Focusing on the structures, she says, gives students an opportunity to lean in without feeling divided by political opinion.

“The goal was to talk about systems and continuity. So I was less interested in digging in on the political issues that differentiated the candidates and was more interested in talking about the structural nature of elections, so that my students could see how the Constitution supported elections or the role of citizenry in elections. Because regardless of political differentiation or whatever policy area that might be hot in this election versus four years from now, the structures that underlie or act as the foundation of the election should be consistent over time, and that is the takeaway I want them to have.”

The results? More civil dialogue. More curiosity. Less chaos.

“I find that it tempers a bit if I’m able to live in that structural way of thinking. And it keeps things a little more calm and, maybe in a weird way, more engaging because it doesn’t turn off or dissuade students who think differently.”

Understanding the structures of government and being able to have civil discourse has taken Shari’s students beyond the classroom. They’re attending city council meetings. They’re hosting public events about zoning regulations. They’re paying attention to social media and leaning into their communities.

“At the end of the day, I just want my students to be engaged citizens in a democracy, and I want to give them the tools to do that. They’re going to do amazing things. I know they will. They already know how to practice civil dialogue. They already see the structures and the importance of them, and they know how to set political opinions aside and work with the person as a human in front of them. And because they have practiced these things here, they’re going to be able to make this a better place for us. All of us.”